Burger Economics

An analysis of the trophic rent flows associated with burger production.

For additional context read: https://roths.substack.com/p/the-true-source-of-secular-stagnation

When considering the flows of production through the economy along the lines of a trophic model, I have previously outlined the example of the effect rising rents have on the prices of various consumer goods such as the humble cheeseburger, which I will now proceed to formalize in a greater degree of depth.

Rents are not simply a matter of the real estate costs of pastures/warehouses/etc, but also other non-material rents such as taxes, permit fees, intellectual property rights licensing, or etc as classical rent seeking behavior. For the purposes of this analysis, rent is essentially any non labor based economic extraction of value derived from property rights enforced by the state. In moderation, rents can be used as an effective method of allocating scarce material resources and the revenues generated from such activities can be applied towards positive and socially necessary ends such as productive investment, stewardship of natural resources, research, or other positive endeavors. Regardless of what ends the rent revenues are put towards, the model applies nonetheless though.

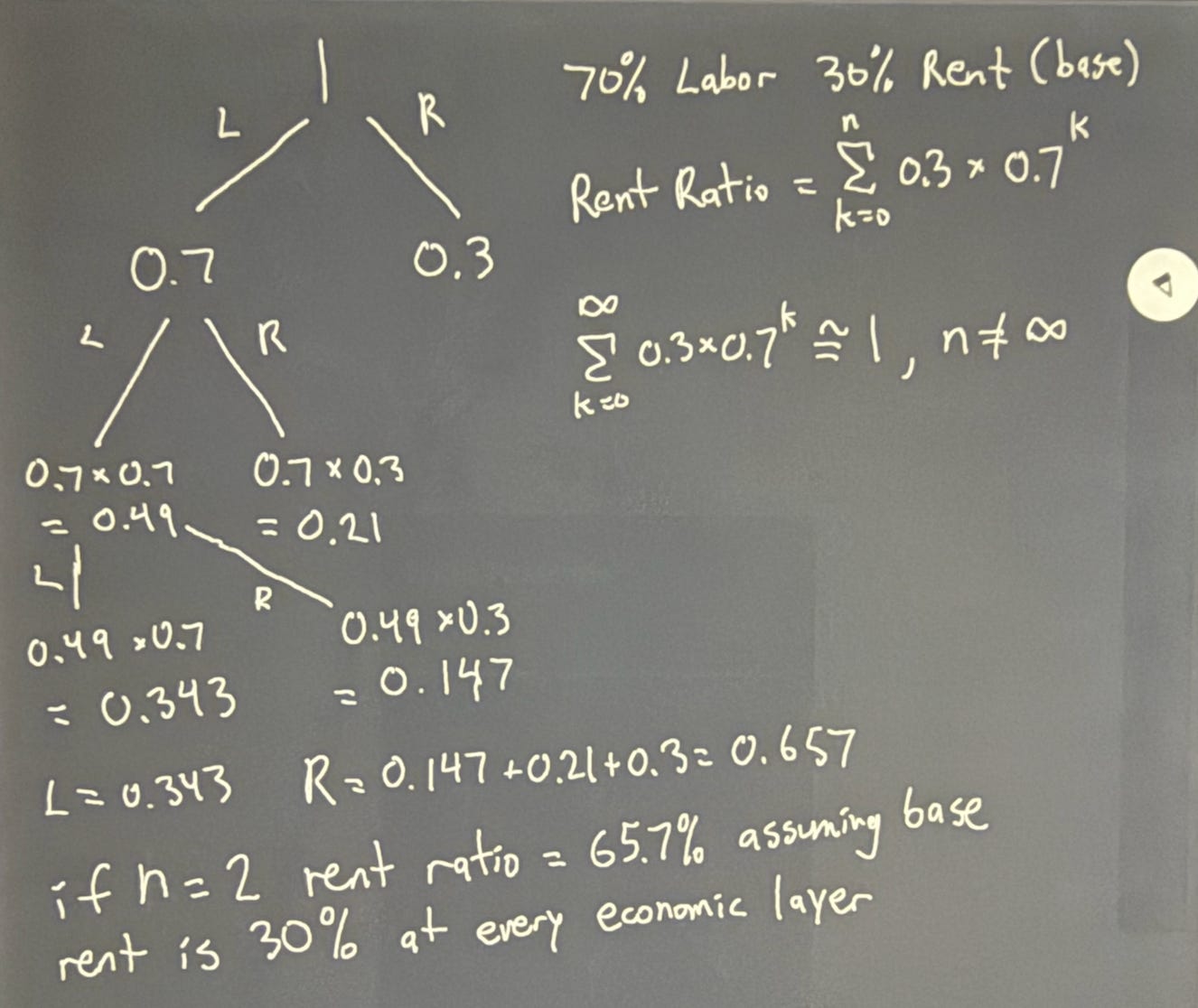

If one were to assume a generalized worker who gets paid a wage, with 30% of it being extracted via various forms of rent either based on property/tax/etc, a rent value extraction ratio can be derived from the share of final product value that goes to the laborer compared to the recipient of rent revenues.

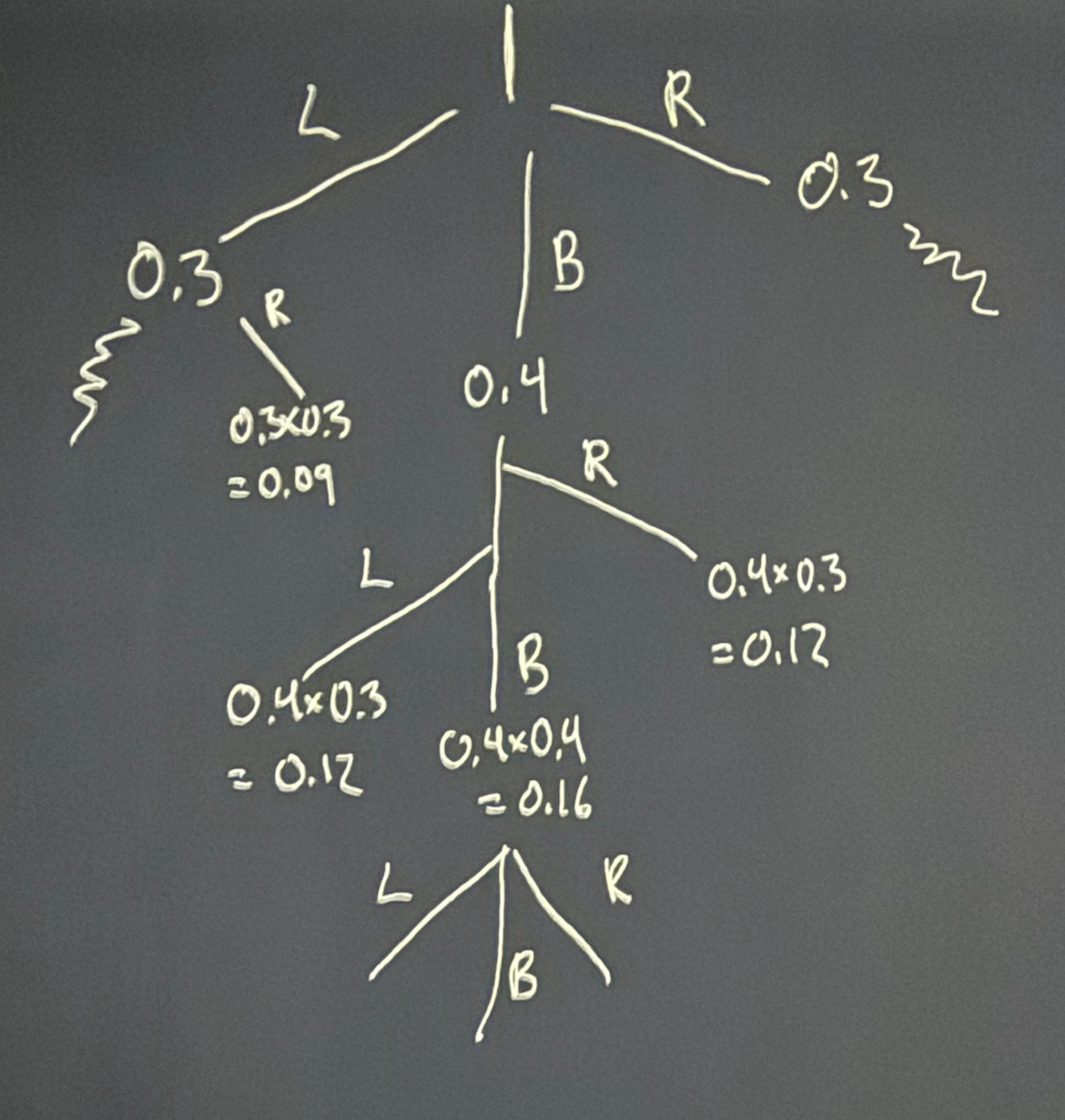

To preempt the obvious critiques of this model, in many ways this is dramatically oversimplified and is not a direct one to one representation of the real world economy. For starters there is a great deal of variance of rent and labor prices at various stages of the supply chain based on conditions of supply and demand, most of the time resulting in a real world rent ratio greater or less than 30% for every time working labor is applied. In addition, rather than being strictly vertical only, there can be parallel branches of economic activity that eventually converge horizontally upon synthesis of the final product, such as with the parallel supply chains of burger buns and beef patties. Finally, for every stage of production there is not only labor and rent costs but also the base input, which is in of itself a result of labor, rent, and another base input.

To and try and extrapolate this to the furthest possible extent you would have to model the rents that the laborer pays, the products that the laborer buys which have their own labor/base input/rent costs, the base input’s labor/rent/upstream base input portions, alongside where the rent is spent in the economy. Boiling this all down to its core fundamentals in a manner that comprehensively demonstrates the full extent of the process by which a consumer buys a cheeseburger with perfect accuracy would not only require outlining the precise details of the modern supply chain required for producing a cheeseburger, but also the historical context by which many of the machines for mass production were made. Eventually a truly faithful and fully comprehensive description of the economy in such a structure would not only have to include a large amount of private company data that is proprietary, but also a great deal of information that is simply impossible to access, including the economic ratios by which Caveman Grug first picked berries for Ug to make him a sharpened wooden spear.

Obviously such an economic modelling project is outside the scope of this article. We are primarily concerned with the fairly narrow scope of determining rough ballpark numbers of how much of a final product’s productive value is captured by rent extracting power elites within government or business who then proceed to decide how to allocate the resources instead of the common man getting the choice. For this purpose a 30% trophic layer rent ratio is a fairly reasonable approximation, albeit in many cases under the real world value derived from taxes and landlord rents combined.

Now back to burgers, assuming a production chain along the lines of:

Farming grains for use as cattle feed

Raising cows on pasture and taking care of them

Butchering the cow into raw meat and other products

Processing the raw meat into frozen burger patties

Cooking the patties and serving cheeseburgers to customers

Gig economy worker picking up food and sending it to final customer

The process of sending a burger to someone’s home would imply a minimum n value 5 (5 additional layers of economic abstraction on top of the basic layer distribution). The real value is probably higher since this probably doesn’t account for the steps associated with shipping and warehousing, but not any lower. Thus when summing up the ratios for each step:

0.3 + 0.21 + 0.147 + 0.1029 + 0.07203 + 0.050421 = 0.882351, or about 88% rent ratio

Naturally, with ratios such as these in play in the economy one might wonder how exactly commercial enterprises manage to compete at all. The answer is that even if rent ends up capturing the value from various trophic layers of economic activity, these producers are usually still significantly more efficient and productive than the customer would be in procuring these goods for themselves, through specialization of process, larger economies of scale, and capital expenditures into machine tooling. Ultimately both the government and big business end up being mutually dependent on each other as they both have a vested stake in being able to profitably extract these resources, which they would otherwise be unable to do as effectively. Thus the government issues forth regulations and subsidies to make sure as much of the economy is dominated by high capital expenditure mass production enterprises as possible because they are easier to tax and exert control over, and the big businesses themselves have their bottom line fundamentally reliant on the aid of the government to keep them competitive artificially. If consumers are getting their food from Mr. Wong selling noodles out the back of his van instead of a restaurant chain, even if the real economic activity is still present in the physical world it is effectively invisible to the state and far more difficult to tax.

While most of the above processes outlined are significantly more productive than someone doing it on their own, or at minimum are able to arbitrage by using low cost labor as an input to get costs sufficiently low, the process of basically hiring a private taxi to deliver a burger to you in particular ends up being horrifically economically inefficient. To help illustrate this point I will outline a comparative case study.

Once upon a time in Summer 2024 I was moving out to a new apartment, and didn’t want to cook at home because of logistical concerns with having to empty out my fridge/etc. Thus I decided to do a little bit of time keeping to measure how long it took for me to drive to McDonalds, get my food, and drive back home. My order of choice was the $5 combo (technically $5.30 after sales tax) including a Mcdouble, small fries, 4 nuggets, and a small Dr Pepper. For the purposes of a fair comparison I will not account for theoretically unlimited soda refills. The time it took for me to order the meal off of the mobile at home and then drive to McDonalds was 6 minutes, it took two minutes for my food to be ready, and driving back home took 9 minutes because left turns are less efficient traffic wise than right turns. In total, there were 15 minutes of active labor (driving), 2 minutes of waiting, and $5.30 required for me to get my meal, eat it, and come home.

When I opened up the Ubereats app to do a comparative cost analysis, not only was the $5 combo option not available, the items added together came to a price of about $19.46 before including any tip. I should note as a caveat that I was able to observe price fluctuations as a result of their algorithmic pricing, but have only included the first set of prices I was presented with. Given the conditions and context, the labor time of driving would have to be priced at $56.64 an hour post tax, or $117,811 a year assuming a 40 hour work week. Accounting for federal and state income taxes/etc would mean you would have to make about $167k, aka be at the top 10% of income in the US to reach labor price parity. Obviously this is absurd, as everyone is either not making enough money for this to remotely make any sense, or has access to far better alternatives for the money that they’d pay. I suspect the Ubereats algorithm is specifically overcharging for McDonalds in particular since anyone who does this isn’t going to be a rational consumer in the first place. At the end of the day though most of the reason this service is so expensive is largely because of the massive overhead associated with the upkeep requirements of the driver alongside the digital platform itself and all the well paid engineers required to keep it running.

While this is fairly low hanging fruit, it does help to illustrate an example where peeling back a layer of trophic economic abstraction results in significant consumer savings. But this can be extended out further into deeper optimizations with a little elbow grease. For example, instead of relying upon the McDonald’s restaurant to do the service of taking frozen food products from the factory and deep frying them for you, you can instead buy frozen fast food products from a grocery store and put them into an air fryer with roughly equivalent results in quality or better, and significantly lower cost. Even as far as time savings go, by buying a larger volume of food from the grocery and then cooking it yourself you save on labor time in addition to money, all the while avoiding paying for more rents extracted either from land, taxes, or other sources. As a result, the simple invention of the air fryer as an efficient low cost high power convection oven theoretically threatens the business model of any fast food chain that relies on reheating frozen foods.

The vast majority probably aren’t able or inclined to start farming their own wheat from scratch, especially when doing so would require competing with heavily subsidized agribusiness. But even for relatively little cost and time spent learning one can gain significant cost optimizations without decreasing the quality or quantity of their consumption through acquiring cheap low capex tools to increase production efficiency.

For example, rather than constantly buy canned sparkling water from the store and pay the overhead associated with the high capex shipping/bottling/storing/manufacturing process, I simply opted to buy a Sodastream along with a CGA320 adapter hose in order to avoid being ripped off from having to buy overpriced OEM CO2 tanks. In the wise words of the adapter hose vendor, “enjoy bubble water without fear of expensive”. Combined with a Brita filter to make my tap water palatable and buying said 5 lb CGA320 tank from a CO2 supply shop, I can carbonate my own sparkling water very efficiently and add lemon juice or syrups to it as I desire for a very low price and negligible amounts of labor on my end required, successfully removing another trophic layer of rent extraction and costs, operating along the principles of the lean manufacturing/kanban methodology pioneered by Edwards Deming. Any labor that you do for yourself isn’t taxed in the same way that wage labor is.

Of course, this could be extended even further into a full blown economic lean production revolution against the current status quo. Production efficiency can be further increased by bolstering volumes through trading goods to members of your local community such as friends or family, with each barter or transaction done without the high overhead of an official business’s rent costs or payroll tax through economic informalization, putting the workers on an even playing field with tax dodging power elites. Going further beyond the example of the air fryer, its theoretically possible someone could start growing potatoes in their land, buy a Chinese potato slicer, and deep fry french fries for their neighbors in an economically viable manner through informal trading if they successfully streamlined production enough. For a working class person whose wages aren’t particularly high, independent low-volume production is potentially especially lucrative if they can get enough sustained business volume.

For more advanced goods currently beyond the capability of easy access home production, development can be pioneered by a vanguard of technocrats leading the way through engineering low cost open source production solutions, and documenting them well enough to be as accessible as possible in a manner similar to how open source software is developed. While this may not be extensible to every category, especially nuclear reactors or semiconductors, progress can nonetheless be made in making more and more of the economy’s productive enterprises accessible to the public, gradually making the world a better place through improved documentation of low capital expenditure production.